Richard Wydeville, Earl Rivers, KG, 1405-1469

£20.00

Wydeville was father-in-law of the Yorkist Edward IV. Nobles opposed to Rivers initiated the uprising that temporarily drove Edward into exile in 1470; fought with distinction in the Hundred Years’ War and married the wealthy Jacquetta of Luxembourg, Duchess of Bedford (scroll down for a more detailed Description)

Print published 1962 © Hugh Evelyn Limited; drawn by by John Mollo (1931-2017)

Print size: c. 36 x 53 cm [14″ x 21″] (may vary slightly from printers’ cut 50 years ago)

Printed on heavy white matt cartridge paper (157 g/sm²).

Print is LARGE size – shipping is the same for 1 to 10 prints (based on largest print size in your order) – see Shipping & Returns.

In stock

- Satisfaction Guaranteed

- No Hassle Refunds (see Shipping and returns)

- Secure Payments

Description

SUMMARY

Rivers was a minor English nobleman who married (way above his station) the widowed Duchess of Bedford, Jacquetta, daughter of Peter of Luxembourg. They had met when Wydeville was in service to the Duke. Close to the Royal Court, Jacquetta’s (and so Wydeville’s) influence increased further when Henry VI married Margaret of Anjou whose uncle was Jacquetta’s brother-in-law. The Wydeville (Rivers) marriage produced a reportedly beautiful daughter, Elizabeth, who married Sir John Grey shortly before he was killed at the battle of St. Albans in 1461, the same year King Edward IV seized the crown. 3 years later the King happened to stay in a castle where Elizabeth was also staying. They married secretly much to the embarrassment and annoyance of the Earl of Warwick (The Kingmaker) who was trying to negotiate a peace with France with the intention of using a suitable marriage for the purpose. The consequence of the marriage was that as the father of Queen consort Elizabeth Woodville, Rivers became the maternal grandfather of Edward V, maternal great-grandfather of Henry VIII and great, great, great, great grandmother of James I of England and James VI of Scotland. He is also a direct ancestor of British prime minister Sir Winston Churchill. The King loaded the Rivers’ with honours and titles so that eventually Warwick exacted his revenge when Rivers was taken at the Battle of Edgecote, 1469, delivered to Warwick and executed without trial.

DETAIL

Richard make-king, Earl of Warwick, is supposed to have taunted Richard Wydeville with the sneer that he had been ‘made by marriage and made lord’, so that it was ‘not his part to have such language of lords being of the king’s blood.’ Certainly the name of Wydeville would probably have made no great mark in the pages of history had not the young and debonair King Edward IV spent a night at a castle where a beautiful young widow called Elizabeth Grey was staying. This widow was one of the daughters of Sir Richard Wydeville, Lord Rivers, a Northamptonshire knight, recently made a baron, who had improved his lot by making a reasonably successful marriage. Edward was captivated by the widow’s charms and abandoning the prudent course of making a political marriage, which was what the Earl of Warwick was planning, he secretly married her, and so found himself committed to bestowing favours on her father and numerous brethren.

Elizabeth’s father had been knighted in 1426 and about ten years later had married Jacquetta, widow of the famous John, Duke of Bedford, brother of King Henry V, and daughter of Pierre de Luxembourg, Comte de St Pol. He was employed in a variety of ways, both in France and at home, and in 1448 was created Baron and Lord de Ryvers. He supported the Lancastrians and was taken prisoner at the battle of Towton. On this occasion he was fortunate enough to escape with his life which was unusual, and a pardon, which was almost unheard of.

No great offices came his way until he became father of the queen. Shortly after his daughter’s marriage was made public he was appointed Treasurer of England and created Earl Rivers. A year later he became Constable for life, his son Anthony having the right of succession. The bestowal of these high honours antagonized Warwick and was doubtless one of the causes of his final volte face when he deserted the Yorkist cause for that of Queen Margaret and the Lancastrians.

As it turned out Rivers became one of Warwick’s victims, for after the triumphant return of Warwick in his new guise as a Lancastrian, Rivers was taken at the battle of Edgecote, delivered up to the king-maker and executed without trial; such was the rough justice meted out to opponents in the wars of the Roses, for there can scarcely have been a man who did not harbour a blood feud he wished to repay.

Though Rivers perished unmourned, his blood was transmitted to the succeeding sovereigns of England by his royal daughter, the great-great-great grandmother of King James I of England and VI of Scotland.

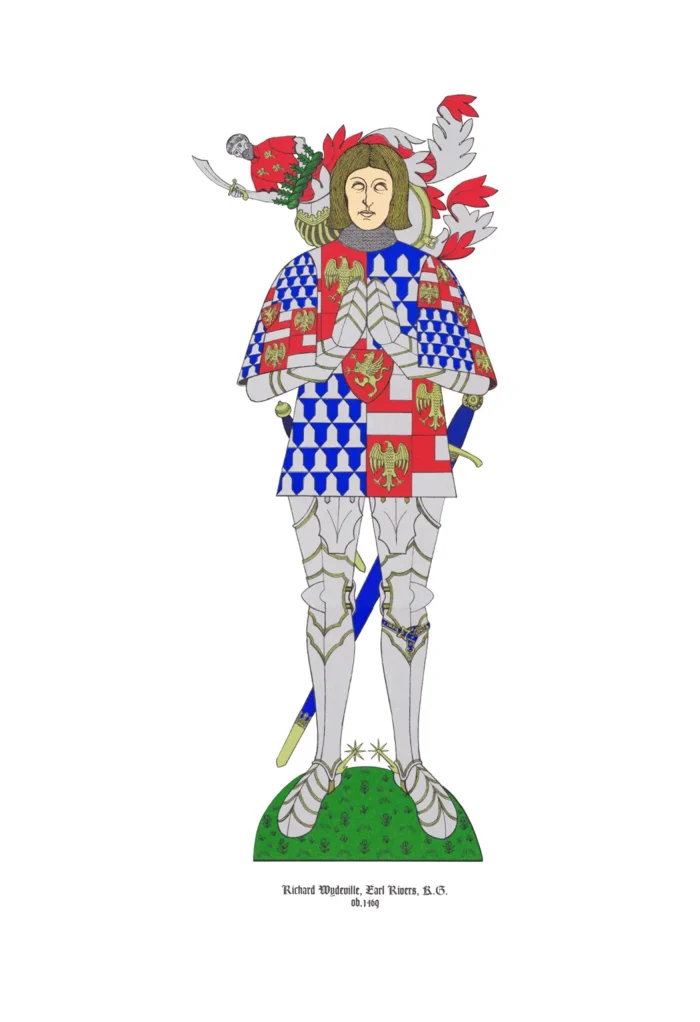

Earl Rivers is shown in a relatively modest harness of armour, for at the time of his death very fanciful armour, with wildly exaggerated and ornamented defensive plates, particularly at the joints, was coming into fashion. He wears a short tabard[1], thus exposing the scalloped tassets[2], with large sleeves, and his leg armour is characterized by the round-toed sabaton[3], which had superseded the ‘winklepicker[4]‘, and by the complex knee defences. The whole ‘helm[5] unit’ represents an artist’s fancy rather than an accurate representation of a useful piece of armour. It is unlikely that the grilled pageant or funerary helm was ever seriously used for other than display purposes. It may have enjoyed a fleeting popularity in the tournament, but generally it is to be met with more in monumental and decorative heraldry. Its use here serves to illustrate the important fact that although the origin of the use of coats of arms may have been primarily due to a need for identification, their survival must be attributed in great measure to the artistic possibilities of arms having been early appreciated. The mantling which adorns the helm is a pure fancy and shows how this feature of an achievement of arms, when wildly exaggerated, is often referred to by the inexpert as ‘seaweed’ or ‘foliage’. The Wydeville crest is a demi-man emerging from holly leaves, dressed in a red coat powdered with gold trefoils and brandishing a falchion[6] in his right hand.

Rivers’ arms and crest appear on his very fine stall plate as a Knight of the Garter, which was probably made at about the same time as he became a companion of this Order, namely in 1450.

The arms are quartered, the first and last quartering being sub-quartered to show Argent[7] a Fess[8] and a Quarter Gules[9] for Wydeville and Gules an Eagle displayed Or[10] (a red eagle on gold) possibly for Prowes, or Gabyon, but the identity of this coat has never been definitely established. It appeared, quartered with Wydeville, on the now non-existent brass of Richard Wydeville, Lord Rivers’ father, but there is no clue as to its provenance. The Wydeville arms, owing to the merging of the two charges, the quarter and the fess, look rather like an ugly red ‘L’. The second and third quarters simply show a field vair[11]. This is one of the heraldic furs and is made up of small skins, alternately blue and white. This coat is for Beauchamp of the west country and commemorates the fact that Rivers’ father married a daughter of John Bedlisgate by an heiress of William Beauchamp of Wellington in Somerset.

In the brass referred to above the arms of Richard’s wife were shown as Bedlisgate (three martels[12] on a bend) quartering Beauchamp. Lord Rivers must have decided to abandon the unimportant Bedlisgate quartering and simply show the well-known Beauchamp coat.

It is possible that his Beauchamp ancestress, of whom he was obviously proud, may have related to the Rivers or Reviers family of Devon and that therefore Wydeville took the unusual title of Rivers. Certainly the gold griffin on red which is placed on an inescutcheon[13] over his arms is used to represent his earldom, although his exact connection, if indeed there be one, with the Rivers family has never been discovered. Rivers’ daughter, Queen Elizabeth, used a shield of six quarterings, the first five being splendid with the heraldry of her mother’s noble line, whilst in the sixth and least quarter she placed her humbler paternal coat.

[1] A short surcoat open at the sides and having short sleeves, worn by a knight over his armour, and emblazoned on the front, back, and sleeves with his armorial bearings.

[2] a piece of plate armour designed to protect the upper thighs.

[3] A broad-toed armed foot-covering worn by warriors in armour.

[4] A shoe with a long-pointed toe.

[5] The great helm or heaume, also called pot helm, bucket helm and barrel helm, is a helmet of the High Middle Ages which arose in the late twelfth century in the context of the Crusades and remained in use until the fourteenth century. The barreled style was used by knights in most European armies between about 1220 to 1350 AD and evolved into the frog-mouth helm to be primarily used during jousting contests.

[6] A broad sword more or less curved with the edge on the convex side.

[7] Silver.

[8] An ordinary formed by two horizontal lines drawn across the middle of the field, and usually containing between them one third of the escutcheon. [An ordinary is a charge of the earliest, simplest, and commonest kind, usually bounded by straight lines, but sometimes engrailed, wavy, indented, etc.]

[9] Red.

[10] Gold.

[11] Varied or variegated in colour.

[12] A hammer; after the 15th c. esp. one used in war.

[13] An escutcheon of pretence, or other small escutcheon, charged on a larger escutcheon.

Additional information

| Dimensions | 37 × 54 cm |

|---|