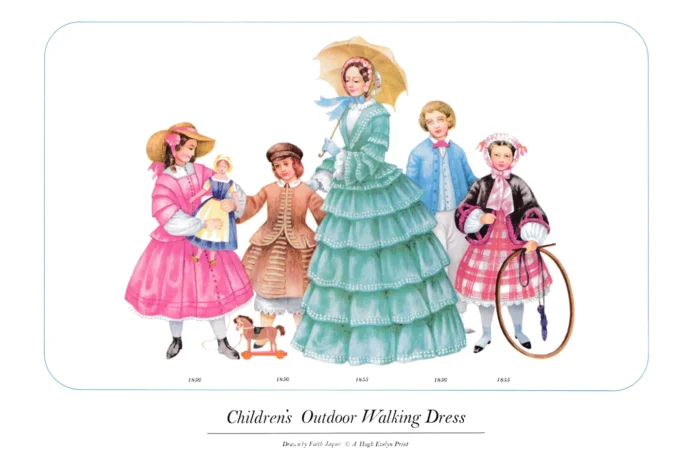

Children’s Outdoor and Walking Dress, 1855-1856

£5.00

Children’s Outdoor and Walking Dress, 1855-1856 (scroll down for a more detailed Description)

Published 1966 by © Hugh Evelyn Limited; drawn by Faith Jaques

Size: c. 38 x 25.5 cm [15″ x 10″] may vary slightly from printers’ cut 50 years ago

Printed on white matt medium cardstock weighing 148 g/sm2

Print is STANDARD size – shipping is the same for 1 to 10 prints (based on largest print size in your order) – see Shipping & Returns.

In stock

- Satisfaction Guaranteed

- No Hassle Refunds (see Shipping and returns)

- Secure Payments

Description

The family unit was at its full strength in the middle of the 19th century; with adherence to a rigid, fundamental religious code and the comfort, health and rights of woman ignored, it was usually large, even if several little offspring found the battle of life too strenuous and returned at an early age to the Golden Gates and singing angels so touchingly depicted on their tombs and obituary cards. Attributing all the evils of adult life to unbridled passions, the quite genuine object of the upbringing of children had been, for many generations, to break these nasty traits before they completely controlled the growing child. The object was worthy if the means excessive, and except in compassion towards those less fortunate than themselves it succeeded in producing a vast number of upright, law-abiding, if priggish, citizens. With all the love in the world Queen Victoria wrote of the difficulty of breaking the wilful spirit of her Dearest Child, the Princess Royal, and found to her sorrow that the character of her eldest son was undentable. Childhood must have been a dull routine for most children, with work and application stressed and playtime strictly rationed. The fact that the pivot round which the family revolved was the mother, who with few serious interests other than her social world could mostly be found in the home, gave the children a sound anchorage and a feeling of safety in their early years, which is one of the brighter impressions of Victorian life. Should the mother be a society woman, then her role would be delegated to a devoted nurse who became the anchor of the children’s lives, in her place. By the 1850’s we notice that a little more awareness of a child’s mind and inclinations had become apparent, through the happy coincidence of the characters of several writers and artists who retained a childlike imagination in adulthood. Books for the young were no longer exclusively moral tales and suddenly sprouted a sense of humour, like Edward Lear’s Nonsense Rhymes, and could be entirely a world of fantasy, such as Alice, or pictured with fun and delicacy by Richard Doyle. Even learning was undertaken with less pain and tears in the early years. Delightful toys began to appear (often made, we regret to say, by children with a ‘deprived’ background). Prince Albert brought over the Christmas tree from Germany where the young appear to have been indulged rather more in the way of presents than in England. There were dolls’ houses, musical boxes, theatres with scenes and actors for whole plays and, above all, beautiful dolls; for the less rich there were cardboard ones with paper dresses, in all the finery of the social world, for the price of 6d. It is from some of these that we know exactly how little, or big, girls were dressed in the 1860’s. On the whole children’s clothes were still a miniature replica of those worn by their parents, minus the hard steel frame to hold out their skirts in the case of the girls. In fashion plates children are made to look sentimental cossetted little dolls; the early photos show us that every effort was made, and with success, to reproduce the solid well-covered look of the drawings, and we know that clothes must have been a heavy burden. A little girl would wear a knitted vest, a chemise all tucked and embroidered, little stays with straps over the shoulders, a flannel petticoat and one or two starched cotton ones with the hem of one padded with the famous horsehair. Her knickers make an interesting revelation of the ideas of hygiene of the period. In imitation of her mother she would wear the long cotton or calico pantaloons that reached to her ankles. As, naturally, with a shorter skirt these white legs picked up the dirt, to save laundering a full garment, separate straight leg pieces were made to button onto a pair of short knickers or were made with a band to fasten above the knee – we conclude – sans knicker! The little dresses were made with tight bodices, with skirts, much pleated and gored, attached to them, while the sleeves followed the same rounded line of adult dress, bell-shaped and fitted at the shoulder. Only for party wear d id little puff sleeves appear and these were placed in low on the should er. With such complicated garments only the rich could have many changes so it was the habit to cover all with delightful little aprons, full like the dress, with the bib front projecting like flaps on the shoulders. The Queen of England ‘s much-written-of home in the Highlands and her family’s doings in Scotland had popularised the tartan patterns for some time, especially for children, and we see them reproduced on velvet, in cotton, wool or silk for every occasion. The combination of predominantly royal-blue tartan and white lace frills, or the Royal Stuart showing several inches of embroidered cotton petticoat, is distressing to the eye, but one is comforted by the thought of what these garments looked like after a party, or of the freedom of the little girl with knicker-legs, only, under her dress. Boys, up to the age of seven, appear like little girls, with skirts ballooning over pantalettes and with little bolero jackets, or tunics. In the mistaken idea of making them ‘quaint’, boys’ fashions have always followed military or naval uniform: short jackets, lots of braid and buttons and even double-fronted. Bigger boys now followed their Fathers’ fashion with the new short jacket, again from the reefer worn by seamen and probably influenced by the Prince of Wales being pushed into the Navy at a tender age. He certainly made it the fashion for men later. Trousers were loose (again, like sailors’ slacks), generally shorter than men’s trousers, and were mostly in a light material. Long stockings were worn, unhealthily gartered above the knee, and for everyday wear ankle boots, often of two-coloured kid or with patent leather toe caps and tops made of soft material, laced or with elastic sides. With candy-striped stockings, and several inches of white pantalettes showing, these little boots made a child look quaint, indeed, but one wonders how much of the humour of their appearance was unconscious. The predominance of hoops, tops and skipping ropes in their pictures encourages one to think that an outdoor life was opening for the child, but it was a long time before the stuffiness of their existence, and clothes, was accepted as the cause of so much youthful illness. Walks at regular intervals, in the parks of towns or in the gardens of country houses, were the rule for the children of the rich, and the middle class kept their children strictly within the walls of the house or private garden until the Second World War levelled the classes and the absence from home of the mother allowed a child to follow its inclinations – and other children – into the street.

Additional information

| Dimensions | 38.1 × 25.5 cm |

|---|