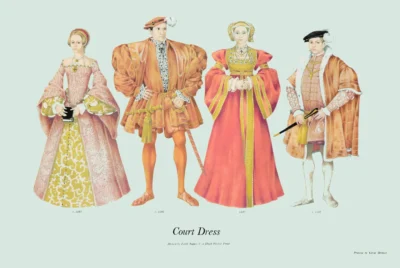

Upper-Class Men’s Dress, 1570-1602

£7.50

Upper-Class Men’s Dress, 1570-1602 (scroll down for a more detailed Description)

Published 1968 by © Hugh Evelyn Limited; drawn by Faith Jaques

Size: c. 38 x 25.5 cm [15″ x 10″] may vary slightly from printers’ cut 50 years ago

Printed on medium cardstock weighing 151 g/sm2 faced in light greyish cyan – lime green (RGB: c. d8e8e0)

Print is STANDARD size – shipping is the same for 1 to 10 prints (based on largest print size in your order) – see Shipping & Returns.

In stock

Description

The British admired the pioneering exploits of the Spanish but with more than a little envy. They soon began to compete in seamanship, exploration and trade. Merchant companies were formed with their own fleets. New trading posts imported textiles in exchange for goods traded. Late Elizabethan embroidery owes their interest to exotic designs of flora and fauna from India and China, while rugs appeared in portraits that were woven in the East. Clothes were stiff in line but had a lighter colour and texture than the early years of the century. Silks from home looms (often Huguenot); brocades from the Netherlands; fine gauzes from the east. Men of most European countries except France looked similar. Despite the ridiculous ballet skirt breeches, heads were alert with close-cut, brushed-back hair, neat pointed beards and moustaches. Full loose breeches were now shorter and inflated with padding to stand out from a constricted waist, emphasizing muscular thighs. These became so popular that the difficulty of sitting caused seats in Elizabeth’s Parliament to be widened. The gorget and breastplate show where the padded-stomach fashion arose: the peascod. The ridged breastplate was made in two planes so a sword would glance off the surface. The eccentricities of heroes were copied, so swaggering curves to the manly stomachs of this era were imitated, by boning and padding the fronts of doublets between the outer material and a fitted lining. By the 1580s the costume reached a peak of exaggeration illustrating the cocksure spirit of the age. Sleeves as well as fronts became padded with two materials pinked and puffed together. Ruffs appeared in the 1560s and grew in height and width as starch was first used to keep them stiff and crisp. The more robust of Elizabeth’s heroes rebelled against ruffs and wore turned-down collars in lawn and lace. Short breeches were irksome so the older man welcomed the sensible Italian knee breeches, called Venetians. These garments had been worn for years by in Germany and Switzerland but were too normal for those wishing to display fashion. After a period of barely hip-length hose, the combination of short stuffed breeches over a long knee-length second pair took composure to wear in public, but here is Sir Walter Raleigh in puffed upper-stocks and canions, as they were called. His son reflects the fashion of the next generation with the long loose breeches and the soft falling collar.

Additional information

| Weight | 0.0147 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 38 × 25.5 cm |