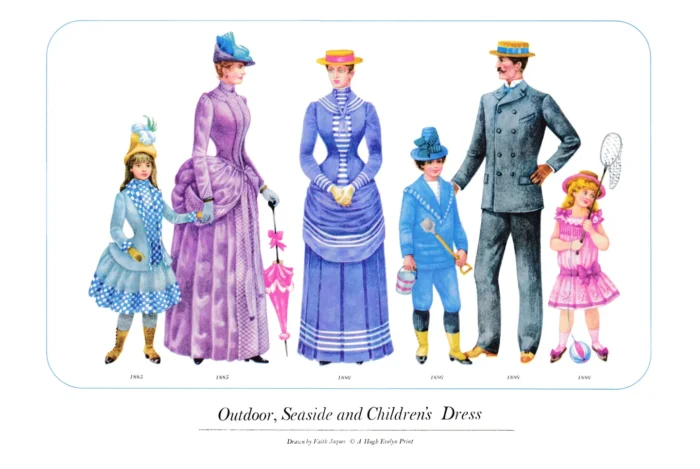

Outdoor, Seaside and Children’s Dress, 1885-1886

£5.00

Outdoor, Seaside and Children’s Dress, 1885-1886 (scroll down for a more detailed Description)

Published 1966 by © Hugh Evelyn Limited; drawn by Faith Jaques

Size: c. 38 x 25.5 cm [15″ x 10″] may vary slightly from printers’ cut 50 years ago

Printed on white matt medium cardstock weighing 148 g/sm2

Print is STANDARD size – shipping is the same for 1 to 10 prints (based on largest print size in your order) – see Shipping & Returns.

In stock

Description

Mechanical mobility, as well as physical, brought the people of the I 880’s into a more modern world with lots more of them doing the things we have absorbed into our daily life as a matter of course. This was a decade of great scientific advancement. The whole scene brightened considerably, with electricity entering the home and more streets losing their Dickensian murkiness in the new light. Even sanitation and piped water had improved, making it possible for more people to be particular about their appearance. It is the Railways that must be given credit for the great democratizing of pleasure and, indirectly, the way people looked. It did not take very long to cover England and the Continent with a great network of railway lines, and to ensure their constant use the idea of regular holidays was strenuously pursued from the 1840’s. Much greater comfort had been offered to travellers by the mid-19th century, with sleeping cars and restaurants on the Continental routes, making long journeys far quicker and more pleasant. The pent-up town-dweller could now have a day at the seaside or a sojourn at the Cote d’ Azur as a regular and comparatively easy matter, and the annual summer holiday became a habit with the great middle class in England. Travelling and staying away is a great wardrobe-freshener and there is no doubt that mobility and the intermingling of people did a lot to raise the standard of general clothes-consciousness. While several English resorts became the playground of the ‘people’ others became known as being exclusive and genteel and were a simple transference of the middle-class population from Kensington or Beckenham to the sea. The famous resorts in northern France were quite frankly showgrounds of the fashionable world and the less smart who were its audience. Everybody with any pretensions to fashion in society, the sporting or theatrical world, gathered here for a definite season which opened officially with a carnival. A satirical description of Trouville in 1886 states that bathing was of minor importance; what was essential was the parade up and down ‘les planches’ at least four times a day, with a different costume for each promenade. The English classified their watering places from very early on, except for ever-individual Brighton which, being so near London, was a place of escape for all classes for short visits. Going by contemporary advertisements the biggest attractions so many resorts had to offer were ‘quiet and refined’. The more contact became possible, the more the effort was made for withdrawing into groups with the same social background. It was from mutual choice that the middle class sought the seaside places away from the riotous, noisy proletariat who, in their turn, would have given very little for the resort offering only ‘sea air, quiet and seclusion’. There was then a certainty of mixing with people of one’s own class and seeing the same sort of clothes as when parading after church on Sunday or attending a theatre or concert. Special provision had been made for the watering place and the healthy bathe, but with such rigid rules of decorum on the beaches very little can have been seen, as far as women were concerned, of the intricate bathing-dresses that with lacing and tight boning were very little different from normal dress anyway. Despite the reluctance to relinquish any of the accustomed bulk of garments the people of the ‘eighties do look more alert and business-like than their predecessors and did make some effort to fit their clothes to circumstances. The greatest boon to man was the light suit in grey flannel that has become so much a part of our lives that it is hard to believe that it ever had a first occasion. Flannel has always been dear to the British heart as it was made from the best wool of that earliest foundation of British economy, the sheep, and was guaranteed to meet all requirements. It was neither too heavy nor too flimsy to lose its shape; it absorbed perspiration while allowing for ventilation and acted as a protection against wind or chill. Another thing it did rather well was to shrink, but this is not advertised. In good grey it fitted in with any weather or surroundings and could be tailored into as smart a suit as any other good cloth. The holiday spirit entered man as he donned his flannels and that symbol of summer leisure. the new hard straw hat. Panamas and soft straws had been worn in the summer and hot climates for many years but this was something novel. The new headgear previously had very exclusive associations, being the individual distinction of the Harrow School boy, and having been so conspicuous during the annual struggles between the great public schools, rowing at Henley, the association of water and summer must have given the hatters the inspiration for a novel form of headgear; thus from its closest connection it was quickly dubbed ‘the boater’. The square-topped crown and flat hard brim gave it a jaunty, wide-awake air that suited the spirit of the times, and very quickly it was adopted as the only summer head covering of the smart young man away from work. The Panama continued for the more mature but eventually the boater conquered all and it was only the old who retained the soft straw hat. Woman in this new trend of masculinity soon had a smaller crowned version produced to compete with the male’s trim sportsman-like headgear. Man’s usual elementary symbolism (illustrated by the unflagging use of the fish on bathroom tiles or vegetables for the kitchen) boosted the boater’s popularity and it soon became the uniform for beach entertainers, bathing attendants and the fishmonger who, although its general popularity waned in the 1920’s, can still be seen wearing it to this day. The same may be said for costume designs for the seaside. Blue and white stripes link up with the Navy and the sea, and the man’s double-breasted jacket reflected the comfort of the seaman’s reefer – a fashion that has never died out, moving to an even closer affinity by the addition of brass buttons. Women’s dress suffered a set-back in its progress towards something more functional with the waist-pinching and padding as fierce as ever. The separate bodice, heavily boned and reinforced, the fronts generally ending in a sharp point as another means of accentuating the small waist, was now always worn over the skirt band. The emphasis at the back was at its most prominent in 1886 with the hard wire cage-bustle tied under the petticoat round the waist. Skirts, at least, were no longer tied in and the slim front silhouette was maintained by goring or fiat pleating the underskirt, the drapery being pulled severely and closely over the hips in what became known as the ‘fishwife’ from the caught-up skirts worn by Scottish fisher girls when gutting their herrings. Luxurious hairdressing had disappeared with the advent of the New Woman. Festooned curls and false chignons had nothing in common with her trim outline and purposeful air. A closely trimmed hair-style, fiat over the ears and pulled into a simple coil or bun, with only the licence of a few curls on the forehead, suited the more masculine tailor-made type. Perched hats carried the straight, tall line still further, with raised crowns, closely curled brims and an assortment of sharp feather or ribbon trimming rising high on the top. It is sad to note that the young still had a long way to go before comfort and suitability were considered essential for a happy healthy childhood. A young girl was such a miniature replica of her mother that she only had to lengthen her skirts to toe level and put up her back hair to be grown up. Until just after the First World War there was no attractive intermediate period between the girl and the woman. For a very small girl the informality of the seaside was just opening the possibilities of short socks and bare legs, but a boy remained decently clad until that lover of youth, the valiant Robert Baden-Powell, offered a new field of activity and uncovered their knees in the early years of the 20th century.

Additional information

| Dimensions | 38.1 × 25.5 cm |

|---|