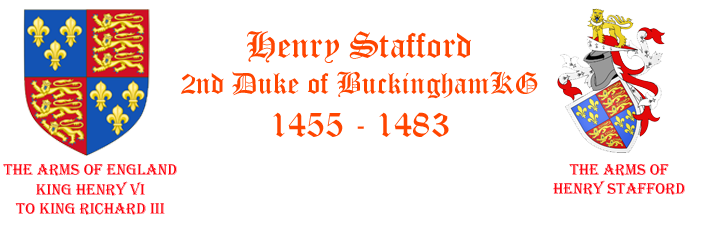

Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, KG, 1455-1483

£35.00

A leading supporter, then opponent, of Richard III; Lancastrian descendant of Edward III. Married Catherine Woodville, sister-in-law of the Yorkist Edward IV (scroll down for a more detailed Description)

Print published 1962 © Hugh Evelyn Limited; drawn by by John Mollo (1931-2017)

Print size: c. 36 x 53 cm [14″ x 21″] (may vary slightly from printers’ cut 50 years ago)

Printed on heavy white matt cartridge paper (157 g/sm²).

Print is LARGE size – shipping is the same for 1 to 10 prints (based on largest print size in your order) – see Shipping & Returns.

In stock

Description

SUMMARY

Upon the death of Edward IV in 1483, Buckingham became the great protagonist of the king’s younger brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester. Buckingham played a large part in the moves that preceded the proclamation of Richard as King Richard III. He helped Gloucester intercept Lord Rivers who had custody of the 13 year old King Edward V and his brother the Duke of York aged 9. He brought them to London, where they disappeared. It is not known to this day whether responsibility for their murder at the Tower of London lay with King Richard III or the Duke of Buckingham. 2 small coffins were found interred there in 1674 and reinterred at Westminster Abbey. Buckingham had suggested (on dubious grounds) that Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth of Wydeville was null and their children (the Princes) therefore bastards. Parliament accepted the theory and offered Richard the Crown in 1472. In one of the great mysteries of English history, despite his high position and obvious trust and support from the King, Buckingham became disaffected with Richard III. This was possibly thanks to Bishop Morton who, a virulent anti-Yorkist, was his prisoner at Brecknock Castle. Buckingham then joined with Henry Tudor and Tudor’s mother, Margaret Beaufort, leading an unsuccessful rebellion in his name. Buckingham was executed for treason by Richard III in the courtyard by Salisbury market-place in 1483. 2 years later the King was killed at Bosworth Field – an event ending the Plantagenet dynasty and the mediaeval era. [King Richard III’s body was found in a car park in 2012 and reinterred in Leicester Cathedral in 2015].

DETAIL

In February 1474, King Edward IV being finally and securely on his throne, it is recorded that the heralds decided that the nineteen-year-old Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, having precedence before all dukes save those descended of the king’s body, was heir to Thomas, Duke of Gloucester, sixth son of King Edward Ill, and so might ‘beire his cootte alone’ in place of the red chevron on gold which was the Stafford coat of arms.

The Duke of Gloucester, known as Thomas of Woodstock, was murdered in 1397 and his only son died two years later, leaving his sisters as co-heirs. The only sister to marry was Anne, who married first Thomas Stafford, and then his brother Edmond, by whom she had a son and heir Humphrey. Thus, when Anne died in 1438 Humphrey became heir to his maternal grandfather. He was created Duke of Buckingham in 1444 and died in 1460. He was succeeded by his grandson Henry, the 2nd Duke.

Thomas of Woodstock had borne the royal arms differenced by a silver bordure and it was these arms which Buckingham assumed, simply altering the French coat from a field powdered with lilies to one bearing three fleurs-de-lys. This simplification had first been made by the King of France and copied in England at the beginning of the reign of King Henry IV.

Buckingham was acknowledged as Lord High Constable by Letters Patent, being ‘a cosyn and heir of blood of Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford’, and as he was a great protagonist of Richard, Duke of Gloucester, he was suitably rewarded when Gloucester became King Richard III. Buckingham played a large part in the moves which preceded the proclamation of Richard as king. After the sudden death of Edward IV he helped Gloucester intercept Lord Rivers, who had custody of the young King Edward V, remove him from his uncle’s care and bring him to London. He also materially assisted Richard when he laid claim to the throne itself, on the rather thin pretext that Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth Wydeville was, for a variety of reasons, null and their children, therefore, bastards.

He followed Shaw’s famous sermon on this theme by a personal appeal of his own addressed to the citizens of London and it is recorded that he was ‘marvellously well spoken’. Although there does not appear to have been any immediate response from the populace, parliament accepted the theory of the nullity of the late king’s marriage and, led by Buckingham, offered Richard the crown. He accepted, with a becoming show of reluctance, and was duly and solemnly crowned, Buckingham officiating as Lord Great Chamberlain and bearing the king’s train. A chronicler tells how he came with a band of retainers all marked with his badge of the Stafford knot, whilst his own horse trap pings were adorned with another of his badges, the flaming cart-wheel.

Richard started his reign with an unusual display of magnanimity towards his enemies and released the Archbishop of York and delivered Bishop Morton into Buckingham’s keeping, an act of grace which probably had more than a little to do with Buckingham’s end. He also made a progress through the midlands where he showed himself an efficient, practical, strong and merciful man. No modern public relations man could have done more for Richard’s ‘image’ than he did for himself, yet the depth and sincerity of the people’s acceptance of him must inevitably be measured by his swift fall.

We now come to one of the great mysteries of history, the defection of Buckingham. No sooner had he acted the king-maker and been well rewarded for his pains with the bestowal of the Bohun lands, with lucrative offices and unusually wide powers, including, at one point, the right to levy forces, than he retired to Brecknock Castle and there plotted to overthrow his friend and master.

It is particularly strange that he should have deserted Richard as he was himself married to Katherine Wydeville, the Queen dowager’s sister, and must have deliberately abandoned that party to join the king’s. Did he sense the tense and restless feeling that trembled through the war-torn land? Did he believe Richard personally responsible for the supposed murder of Edward V and his younger brother in the Tower and find himself unable to stomach so dire a crime? Or did he feel that Richard had been overgenerous to him and might now fear the power with which he had been invested, particularly as he had a slender claim to the throne through his mother, Margaret, heir in her issue of Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset? Most historians agree on one point, which is that when Buckingham went to Brecknock he could not have helped but listen to the persuasive tongue of his prisoner, Bishop Morton.

Morton was an extremely clever and plausible man. Doubtless, he realized that England could not survive under the crumbling feudal system; he scented the sweet fragrance of the renaissance and knew the days of the baronage, decimated first by the French wars and then by the bloody battles of the dynastic quarrel, were numbered; doubtless, too, he envisaged his own role in the building of a new England, ruled by Henry Tudor and was able to paint such an attractive picture to his young gaoler that, his mind already full of doubts, he threw in his lot with Henry, then biding his time across the channel.

A general rising was planned. Buckingham would gather his forces in Wales and in the south and west, whilst Henry Tudor would sail from Brittany with five thousand men. The plan was good and might well have succeeded had not insurrections started before the appointed day. These risings forced Henry to sail sooner than he had planned, and he ran into foul weather and his fleet was dispersed whilst the rivers Wye and Severn flooded, making it impossible for Buckingham to advance. His army disintegrated and he himself fled, a proclaimed traitor with £1,000 on his head.

For a short while a retainer of his gave him shelter, but he was either discovered or betrayed, taken to Salisbury and there executed without trial, one of the enigmas of history and, if ever there were one, a victim of the English climate.

Buckingham was made a Knight of the Garter in 1475 and in his effigy he is shown wearing its famous blue mantle, emblazoned on the left breast with the arms of the Order, the cross of St George within a representation of the garter. Beneath the mantle is a fine harness of armour, many of the elaborate scalloped details being visible.

Additional information

| Weight | 0.0312 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 37 × 54 cm |