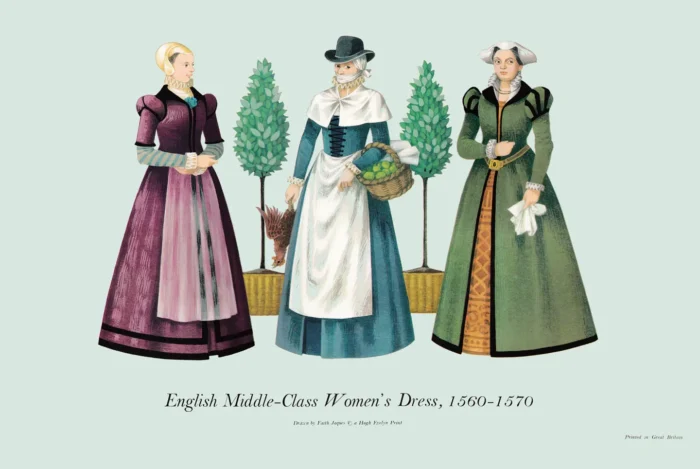

English Middle-Class Women’s Dress, 1560-1570

£7.50

English Middle-Class Women’s Dress, 1560-1570 (scroll down for a more detailed Description)

Published 1968 by © Hugh Evelyn Limited; drawn by Faith Jaques

Size: c. 38 x 25.5 cm [15″ x 10″] may vary slightly from printers’ cut 50 years ago

Printed on medium cardstock weighing 151 g/sm2 faced in light greyish cyan – lime green (RGB: c. d8e8e0)

Print is STANDARD size – shipping is the same for 1 to 10 prints (based on largest print size in your order) – see Shipping & Returns.

In stock

Description

England’s largest commercial industry, wool and woven cloth, was scattered far and wide in villages and hamlets. Britain’s economy was dependent on sheep. The country-side was covered with sheep in the 16th century and labour for shearing, washing, dyeing, fulling and carding went on throughout the island. No backsliding into silks and velvets was permitted by a government who imposed laws forbidding finery and every man had to wear a woollen cap (probably of felt), ‘the statute cap’, on pain of a fine of three shillings and fourpence for every day of default. The English housewife had plenty of local material to satisfy her needs as cottage looms made villages self-supporting. The towns had markets and shops. There were traders going from village to village with their packs, but for an opportunity to see something unusual there were the great Fairs. They gave noise and excitement and an exchange of wholesale and retail commerce. Merchants from all over the country brought and sold. Housewives cut trim and stylish figures in their neat cloth kirtles. French Huguenot weavers had settled in England and brought fresh fashion with their new materials. Spanish fashions came to England when Philip II married Queen Mary in 1554. In a short time shoulders were squared, even puffed, and the Spanish mantle had been adopted as a popular English fashion as the coat-dress. The Spaniards became hated but their fashions continued, even during the Armada. Skirts were worn over a farthingale petticoat with a hoop at the hem to hold the stiff cone shape, and waists were long, trim and generally pointed in front. Though cut separately, bodices were joined to the skirts to ensure a smooth waist and hip line. The countrywoman sometimes closed the bodice by lacing, where the townswoman fastened her overdress like a coat or had a fine piece of embroidery down her corset front in the early version of the stomacher. By the 1560s sleeves were close-fitting but were still the main point of interest in an otherwise severe silhouette. They could still be separate and tied to the armhole by laces, the undersleeve puffing through at the shoulder. In the true Spanish style they were short, puffed and part of the mantle and allowed the straight sleeves of the bodice to show below. Mantles turned back at the neckline into wide collars framing the most characteristic item of Elizabethan dress – the ruffled edge of the partlet or chemise. A wide band held these gathers and gradually became higher and stiffer as the ruff became wider. Despite sumptuary laws, introduced to keep the socially aspiring in their place or as a boost to home trade, merchants’ wives often wore rich material woven miraculously on handlooms or embroidered by themselves. Small, stylized flower and bird patterns now took the place of the florid medieval, diapered designs in weaving or embroidery. From Germany or the Netherlands came the trim little shoulder capes and that very curious fashion of ‘muffling’, or the ‘barbe’, a scarf or handkerchief tied round the lower part of the face and over the mouth. As it added an air of mystery to the face the fashion was retained for many years by older women in the northern countries. Little caps finished the neat costume dipping over the centre parting and closely gripping the ears. In the sprightly masculine trend, tall hats were worn over bonnets or kerchiefs and were finished with a feather or fancy band. The fine skirt was protected by a long linen apron. The socially ambitious might carry an embroidered handkerchief. The British were better fed and better shod than their contemporaries elsewhere: meat was the standard diet so there was plenty of leather to make into boots and shoes while their neighbours still wore wooden sabots.

Additional information

| Weight | 0.0147 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 38 × 25.5 cm |