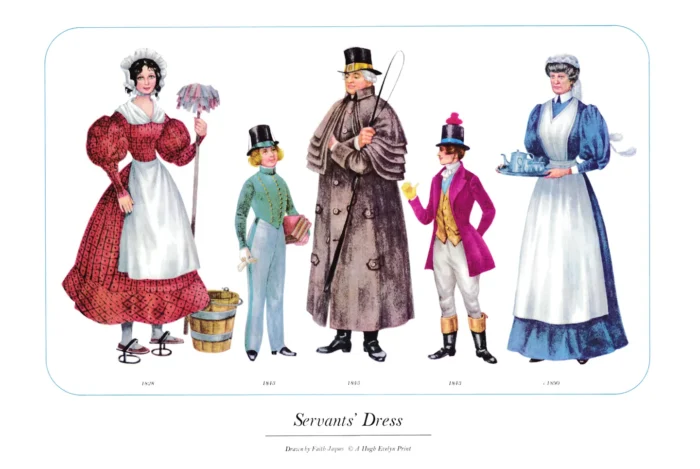

Servant’s Dress, 1828-1890

£12.00

Servant’s Dress, 1828-1890 (scroll down for a more detailed Description)

Published 1966 by © Hugh Evelyn Limited; drawn by Faith Jaques

Size: c. 38 x 25.5 cm [15″ x 10″] may vary slightly from printers’ cut 50 years ago

Printed on white matt medium cardstock weighing 148 g/sm2

Print is STANDARD size – shipping is the same for 1 to 10 prints (based on largest print size in your order) – see Shipping & Returns.

In stock

Description

It is with varied feelings of emotion that we reflect on this once great community, not only whose dress but whose very existence has become a legend with the crinoline and the bustle. A whole stratum of society has disappeared since the Second World War, and even if we illustrated the maidservant of the ‘thirties she would be as curious a type to modern eyes as domestics of a hundred years ago. In the earlier centuries, with no mechanical aids for housework or social benefits for the out-of-work, both the rich and the poor had an acknowledged need of each other; the former in maintaining estates, vast houses and large families, and the latter to earn their keep in an easier way than the hard labour of the fields or mills. Not that it was easy work, but to a child from a country cottage or a hovel in a town, the Big House and good food were a dream compared with the mine or the ‘dark satanic mills’. With our new type snobberies we find it difficult to realize what a step up in the social scale entering domestic service meant in those less socially splintered days, for it was only the more personable young people, of good address, who had a hope of being accepted by the autocrats who really ruled the house, the butler and housekeeper. The pay was a pittance but the perks were many, in the way of better food and handed-down clothes. If one had the stamina to resist years of steam in the kitchen, the long hours of standing and the stairs and attic bedrooms there was a promise of promotion to the important posts of the above-mentioned heads of the household. Long service meant a tiny pension and generally a home, which was something no other labour offered. The companionship of a large staff made for gaiety, and chances of romance below stairs led to many a successful union in the hierarchy, such as the coach man and the parlour-m aid, the butler and the cook, who retired to comparative ease as horse dealers, cab stall owners or inn-keepers. The veterans of the service, even in the 1930′ s, still had happy memories of their early days when as mere children they had enjoyed the good food and merry company of the domestic staff of a great house. The attractive girl with handy fingers could have a more exciting life, and prettier clothes, with a chance to travel, as a ladies’ maid than as a dressmaker’s sweated hand. The gruelling hours of service and the chances of being frozen to death on the outside seat of a coach during a long winter’s journey (as recounted by Osbert Sitwell of an ancestor’s maid) must be taken in comparison with the general hard life of the times. The real evil of domestic service came with the expansion of the middle class with small establishments and the necessity of having a servant as a symbol of gentility and affluence. It must be remembered that, during practically the whole of the century, all the heating and conservancy was provided manually, and it is the horrors of those conditions as well as the modern democratic aversion to rendering a service that has obliterated one section of our community. The housemaid has always worn the accessories of the woman at home, the protecting apron and a cap to cover the hair. Even the housekeeper wore a severe version of the latter until the fashion, in general, went out, but her apron was always of silk and her badge of office the keys suspended from her waist belt. The little maids in Rowlandson’s drawings of the first decade of the 19th century wore the short-sleeved, high-waisted thin dress of her employers, but we are glad to note that separate long sleeves and heavy shawls were part of winter wear. The housemaid of 1828 has the fashionable low-shouldered and large-sleeved dress made, possibly, in the cotton print material that became the accustomed wear for morning housework, being fresh and easily washed. Her ‘pattens’ were the sensible means of keeping her feet dry while slopping down the wide, front door steps and the uneven pavements, or when trotting across a muddy yard from the dairy to the kitchen. As late as 1878, in a book of Beauty, there is a delightful design for wooden pattens suggesting that the condition of roads or paths in parks had not improved and were hardly suitable for the thin shoes, or even the elastic sided boots, available at that time. The coachman is a timeless figure, except for the shape of his hat, right through the century into our own. The rigours of sitting for hours, with only the arms moving, on the high seat of a carriage or coach in all weathers, inspired the heavy top coat made in the hardest face-cloth, so tightly woven that it was almost like leather. The capes appeared in the late 18th century and were added to give extra warmth over the shoulders while leaving the arms free. The young bucks of the early years of the century copied the style in the same way that they aped the hard-living manners of the professional, but the actual garment was so suitable to the purpose that· nothing was ever invented to supplant it. It is the one outfit from the past that is still worn on State occasions or at meetings of coach enthusiasts that looks the least like fancy dress. The wearer, in his hey-day, was a very important member of the staff, as the wellbeing of those essential possessions, the horses, depended on his supervision and had often been bought according to his judgment. In the days of exclusive horse-drawn travel a coachman’s life must have been enviable, on an estate or in a town mews. He had a comfortable cottage or quarters, lived near the beasts he understood so well and had great authority over several underlings, and the jokes all through the century seem to indicate that the horses even took precedence over the convenience of his employers, at times. The little page is a relic of the 18th century and then only for the very smart or rich. George IV was said to have had a page at the ready at his bedside to lift his handkerchief or tell him the time, but we have never learnt if this was night-duty or overtime. In the telephone less days a page must have been kept busy carrying all the interminable letters and notes that his betters managed to write. Lady Caroline Lamb is supposed to have effected an entry into Byron’s chambers dressed as a page (in silver braided jacket and tight scarlet pantaloons), having caused such delightful scandal by haunting him previously without any disguise. The page’s uniform with the tight braided trousers and short military jacket with its rows of converging buttons, was based on the Hussars’ romantic outfit; like so many of the costumes in the early war-ridden years of the century, especially those of children with the idea of making them look ‘quaint’. Although in these democratic days it is doubtful if anybody employs a private page we can all have a vicarious pleasure in patronising his descendant who has retained his uniform – the hotel bell-boy or messenger. The groom is something most evocative of the 1830’s or ‘forties. Grown men had long had their duties, looking after the horses and accompanying the coach or carriage, but with the introduction of the very light, high-wheeled phaeton, suitable for only one or two passengers, it became the practice to employ a page as groom, perched precariously on the tiny seat at the back, and to hold the high-spirited horses when standing. His costume, again a nostalgic continuation of an older fashion, aped the attractive clothes of the sporting buck. In the 1840’s the groom was the final touch of theatrical exhibitionism to the dashing outfit of the glorious dandy and acted not only as a minder of horses but also as page and messenger as well. In France, where the dandy’s propensities had earned him the name of ‘lion’, the groom became known as his ‘˜tiger’ (a designation that was also adopted in England), derived possibly from the black-and-yellow striped waistcoat he sometimes wore. The incongruity of a minute boy – or animal – dressed up and behaving beyond his years or understanding has always aroused our most sentimental reactions. The large dog beside his master in a low, sleek racing-car has quite a psychological affinity with the little tiger, arms folded, miraculously balancing on the high seat of a phaeton. The tears of nostalgia almost prevent the writing of the description of that stalwart figure, the parlour-maid, as it is suddenly realised that it, too, must be in the past tense. The male figures in our Plate had gone, except in the vestigial sense, before living memory, but the parlour-maid gave grace and tone to an establishment well within the experience of the middle-aged, and it is still a rare and breath-taking occasion to have a door opened or be served at table by a veteran of the species. Her’s was a superior position under the butler, second only to the housekeeper, and in a smaller house there was great rivalry for power between the parlour-maid and the cook. She was addressed by her surname and Mrs Beeton lists a formidable round of duties for gracious living that are disgracefully scamped in the modern house hold. Again the uniform stems from the usual wear of a female at home. The cap and apron were not the badge of a menial but the remains of a general sensible fashion. Dresses were generally dark and followed the line of the prevailing fashion, even to the crinoline frame, if Punch is to be believed, and most of them sported the dress improver in the days when woman stuck out at the back. Our figure is wearing the large sleeves and the masculine collar and cuffs of the ‘nineties, a period when the position was at full strength. It is difficult to conjure up a more attractive or satisfying picture than of a door opening in a pretty room and the entrance of that stately figure, in the becoming cap and apron, carrying the silver tray and service, sparkling in the firelight, for the drawing room afternoon tea.

Additional information

| Dimensions | 38.1 × 25.5 cm |

|---|