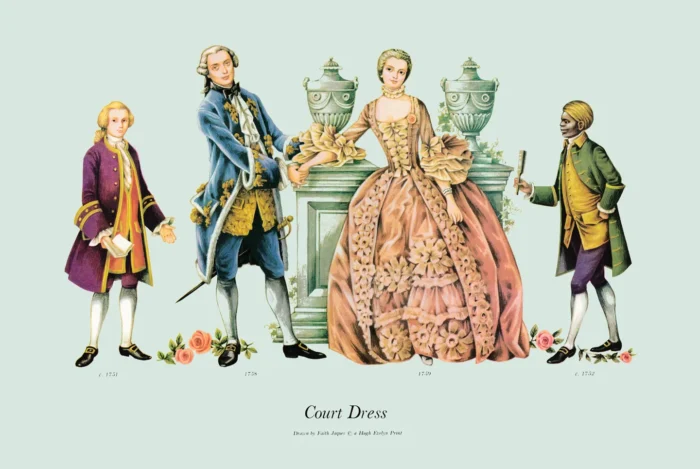

Court Dress, 1751-1759

£15.00

Court Dress, 1751-1759 (scroll down for a more detailed Description)

Published 1967 by © Hugh Evelyn Limited; drawn by Faith Jaques

Size: c. 38 x 25.5 cm [15″ x 10″] may vary slightly from printers’ cut 50 years ago

Printed on medium cardstock weighing 151 g/sm2 faced in light greyish cyan – lime green (RGB: c. d8e8e0)

Print is STANDARD size – shipping is the same for 1 to 10 prints (based on largest print size in your order) – see Shipping & Returns.

In stock

Description

It is doubtful if any woman has ever left such an indelible mark on history as la Pompadour. They have become legends by causing wars, stirred emotions or encouraged thought by beauty or talent, but none has combined all these activities with such taste and visual sensibility that her name has become the symbol not only for the life of a period but the look. An iron will and stamina are other qualities to which Madame de Pompadour could lay claim, since at that period, unfortunately, to have real influence on events it was necessary to become the mistress of the King of France. Modern film stars and pop singers are luckier in having more scope with no strings. Ethically debased though the purpose was, we must be grateful that the political faction, who saw her potentialities and had her trained from early youth in all the social accomplishments as a fifth column at court, developed talents in her that she was able to put to wider use than the amusement of a clot of a king. Jeanne de Pompadour did not make her environment at Versailles: the exclusive, hot-house atmosphere was there as a legacy from the days of Louis XIV, but from the time she entered court circles her exquisite and refining influence prevented it from descending to blatant vulgarity. The very peculiar nature of the French court, exclusive and extravagant with a wealth of original talent to supply its needs, made it possible to produce a pattern of life enviable to the rest of the materialistic world. The only drawback for that birth-conscious nation was that fate had denied it the right type of personalities as heirs to the throne. It is ironic that the woman who enabled it to keep its comfortable lead was a member of the hated middle class and a thorn in the side of every aristocrat forced to acknowledge her position. Having been divorced so long from things spiritual, the French court was blissfully unaware of matters of the soul and could happily devote its entire energies to the enjoyment of physical pleasures, and Madame de Pompadour was just the girl to cultivate this pursuit to a fine art. The perfection of the Rococo period is purely material. Its painters, by a curious coincidence, were the offspring of skilled craftsmen, and although the sublime is lamentably absent from their work they have left us a perfect record of physical joy and the little details of the surroundings that make it appear so entrancing. With the accent on sensual pleasure no stone was left unturned to enhance physical beauty. Small and delicate herself, Madame de Pompadour saw to it that by direct encouragement of artists and craftsmen a suitable frame was made for her personality, which was so compelling that even the most antipathetic of the French nobles were soon following her taste in Sevres porcelain, her dainty furniture and, above all, her choice of material and dress. This veered towards simplicity in a very decorated period, and her famous hairstyle must have put a strain on all but those with the suitable features. The old sacque dress that had done such good service over the past two decades was still in favour as a négligé but was too droopy and obscuring to display the spruce figures that now made themselves noticed in the fashionable world. The attractive sweep of the Watteau pleats was so dearly beloved that it lasted till the I780’s but the well boned bodice was now made to fit closely, all round the body, with a lining under the pleats, and was cut separately from the front widths of the skirt which was gathered tightly into the waist. The overdress effect remained the favourite style but no longer hung loose like a coat, the fronts being fastened to the stomacher, or underbodice, which lay over the under-skirt in a sharp point and was, in France, generally decorated with rows of graduated bows. Corsets were universally worn, whaleboned and beautifully fitted in small sections to assist the smooth look of the long lean torso. Sleeves were a triumph of design. These had been long-fitting ones trimmed with lace frills at the wrist, elbow sleeves with rows of lace ruffles from just below the shoulder-line, or, most usual, long bell sleeves turned back to make a cuff, or folded upon themselves, more narrowly in front, to give the appearance of a pleated, shaped cuff over the lawn and lace of the chemise. The most beautiful line, which perfected the silhouette of the whole figure – the narrow top swelling out and swept back – was the fitting elbow sleeve with one or more circularly cut, gathered frill, narrow in width in front and falling longer at the back to be repeated with lace frills of the same cut under neath. The favourite trimming was ruching of various widths, which finished every edge and ornamented the skirts in interwoven designs. The encumbrance and inconvenience of the great square panniers gave way in the 1750’s to a softer more manageable line, by means of a hooped knee-length petticoat which was quickly followed by the bright idea of boned side-pads tied round the waist like a bustle over each hip. The wide panniers were then only retained for full ceremonial court wear when, it appears, intense physical discomfort for the sake of prestige was meekly endured by all. Black pages dressed in the latest European fashion and treated like pet monkeys were considered a quaint and amusing foil for fragile white beauty. The thriving French slave trade – though not in the rosy position of the English with the shipment of half the world’s demands for this rich commodity – made the supply abundant and cheap. Male clothes underwent a considerable change half way through the 18th century. Gone were the ballet-dance lines of the Watteau period and, although still decorated, coats began to take on the business-like and close-fitting cut of modern clothes. The wide stiffened skirts of the coat had proved themselves a nuisance to all but exquisites. The man of action, especially in England where riding was of such importance, had already begun to turn the corners and button them out of the way. This revealed a contrasting lining of which much play was made in army uniforms and later led to the idea of turning back the neck as lapels. The cut-off effect was found so convenient that very shortly all coats were cut away, the fullness at the side seams reduced to a single pleat and the whole garment given a swept-back line. Following the slimmer cut of the body, sleeves became narrower, cuffs and pockets smaller and the decoration reduced to braid, frogs and tassels. The waistcoat which was still embroidered or of rich brocade was becoming shorter as the century advanced. Altogether a man began to look more alert and 1 like a lounger, but it was some time before the more decorative French put themselves into plain suits of good English cloth. That it was not all eternal summer in this halcyon period is given away by a few pictures in which full fur linings appear as edging to the smart cutaway coats. One facet of the diamond-cut character of Madame de Pompadour that is not so well known is the intelligent curiosity that led her to encourage the writers of Diderot’s famous French encyclopaedia. As a woman of the people she was excited by their inflammatory, radical contributions (little knowing that they would inspire the spirit of the Revolution that swept away the social order of which she had been such an ornament) but she was more immediately concerned with the information imparted by their articles on general knowledge. They not only widened the education of her own generation but have left us a complete picture of the science, industry and domestic life of the 18th century, and as far as costume is concerned there can be no argument as to how wigs were dressed or coats were cut in the time of Louis XV.

Additional information

| Weight | 0.0143 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 38 × 25.5 cm |