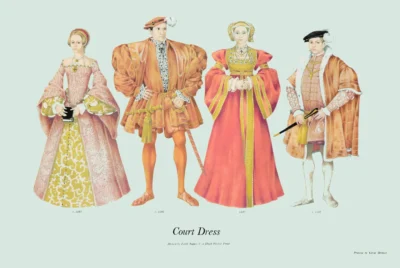

Court and Country Dress, 1710-1719

£15.00

Court and Country Dress, 1710-1717 (scroll down for a more detailed Description)

Published 1967 by © Hugh Evelyn Limited; drawn by Faith Jaques

Size: c. 38 x 25.5 cm [15″ x 10″] may vary slightly from printers’ cut 50 years ago

Printed on medium cardstock weighing 151 g/sm2 faced in light greyish cyan – lime green (RGB: c. d8e8e0)

Print is STANDARD size – shipping is the same for 1 to 10 prints (based on largest print size in your order) – see Shipping & Returns.

In stock

Description

The hold over Europe of French culture was as strong as ever when the 18th century began, but more from habit than from inspiration. The taste and disposition of the ageing Maintenon, her influence over the king, and his own lack of interest for any more experiment, had brought the arts to a state of stagnation, and costume was in the doldrums for nearly thirty years. Baroque art had blown itself out to its fullest extent and clothes, likewise, had no room for another swag, festoon or tassel. The next step could only be towards a complete change, but while the autocrat Louis XIV still held control, that was completely out of the question. The stiff-backed, tedious code of etiquette brought to perfection by Louis himself, as a revulsion from the brutal manners of his youth, when added to a new primness of moral behaviour, had a strong reflection in the armour-plated, tight-laced dresses of the women. The male withdrew so impersonally into his outer shell that only the most remarkable features are recognizable in portraits, peeping out of the jungle of periwig, and the figures inside the heavily reinforced, beskirted might just as well be dummies. The only concession to change in women’s dress was in a little softness, with the skirt fullness gathered into the waist instead of being gored, which had given it a triangular shape from the long tight bodice. It is said that even Louis had shown his weariness on several occasions for the ‘˜fontange’ as the head-dress had grown to monstrous heights with so much metal-work to keep the frills erect that a French wit had suggested that hairdressers should also be blacksmiths! The reaction of the court beauties was to dip the fan-shaped frills almost horizontally, and unbecomingly, before the fashion disappeared through (and it is difficult to believe) the appearance of an English duchess at the court of Versailles, wearing her hair ported in the middle and softly dressed close to her head. The king was so impressed that his admiration and caustic comment regarding the head-dresses of his own ladies furled their sails overnight. A style does not necessarily originate in the country that makes it the vogue for general wear, nor need the originator be recognized as fashionable. English women have seldom been credited with chic but there have always been a few characters of beauty and independence who wore what they liked with great distinction. It is in this rigid period, strangely enough, when the general status of woman was at a low ebb, that we see the first faint effort to exert her rights and individuality which had such a distinct bearing on her appearance. The tactics employed were as varied as the complicated psychological urge that brought them into being. To achieve equal rights with man, mentally and materially, without losing the delight of a special physical relationship, is a knotty problem that has still to be worked out satisfactorily. The French method in woman’s first attempts to assert her identity, in the late 17th century, was to prove equality of intellect, resulting in the famous Salons where already established women of fashion entertained the thinkers of the day. Many words and much scandal were exchanged but the effort had no effect whatsoever on woman’s appearance as fascination was the bait and the movement never left the drawing-rooms. A more primitive gambit was to imitate the male, and even this had a dual means of expression: as a provocation, by wearing men’s attire to accentuate female characteristics and frailty, or by finding some means to equal his physical prowess. Both urges had some satisfaction in a very restricted field – in riding. As the means of asserting independence, over many centuries, the symbol of woman’s emancipation should really be the horse. Women have always ridden; even the ancient Greeks permitted them to race, clad as lightly as the men, but after those more broad-minded days a special costume for the exercise seems to have escaped the interest of designers. A farthingale was not the most suitable or elegant of costumes for sitting on a horse. When male clothes became increasingly feminine in the mid-17th century, the golden opportunity of levelling the appearance of the sexes was not missed by the brighter elements in the courts of either France or England. Very provocative was Madame de Montespan’s show-stopping turn-out for one of the equestrian entertainments at Versailles which was matched, in intention, by that of Frances Stewart (of the Britannia-onthe-penny fame) at the court of Charles II. Her military doublet, periwig and feathered hat undoubtedly had the right effect in some quarters, though Samuel Pepys plaintively recorded that ‘at no point could the wearer be taken for a woman’! The other variation on the same theme brought into being the ‘horsey woman’. Mounted, she could compete physically with man (and look very dashing, withal) and, from the time we first get a glimpse of her in the plays of Congreve, we follow her, booted and whip-flicking through two centuries, until as the New Woman she changed her steed for the bicycle. In the early 18th century her riding costume was identical with male attire, except for the long, wide skirt to the habit. The coat, open to show the laced waistcoat, and the carelessly tied ‘steinkirk’ topped by a full periwig, could all have been made for a man, and it is interesting to note that the coat pockets are still vertically placed, for easier use while seated on a horse. It was not until the 1720’s that much change took place in men’s costume. Coats had tended to become plainer, with only braid and buttons outlining the edges and pockets, leaving to the waistcoats all the richness of brocade and embroideries. It was about this time, too, that the Englishman began to wear more extensively the type of suit that was to become the pattern for men’s wear eighty years later, made from what had been England ‘s greatest economic asset over many centuries – fine woollen cloth. This was indeed an innovation since coat, waistcoat and breeches could all be made of the same material and with the substitution of riding boots for the buckled shoes could be worn for various occasions with fine effect. Fundamentally of a sober nature and enjoying an outdoor life, the Englishman had always inclined to less flamboyant clothes and, from now on, silks, satins and embroidery were worn only by fops and for formal occasions. The periwig gradually became less engulfing, hardly reaching to the shoulders, with the back hair tied with a ribbon bow or caught up into a bag. A grey head, showing age and experience, was much in favour at the dawn of the Age of Wisdom. For those who had acquired the latter but had lost the means of showing them, wigs sprinkled with rice powder gave back that air of distinction. So becoming was the fashion found to be that, before long, young and old were busily powdering, in a vogue that lasted well into the century.

Additional information

| Weight | 0.0143 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 38 × 25.5 cm |