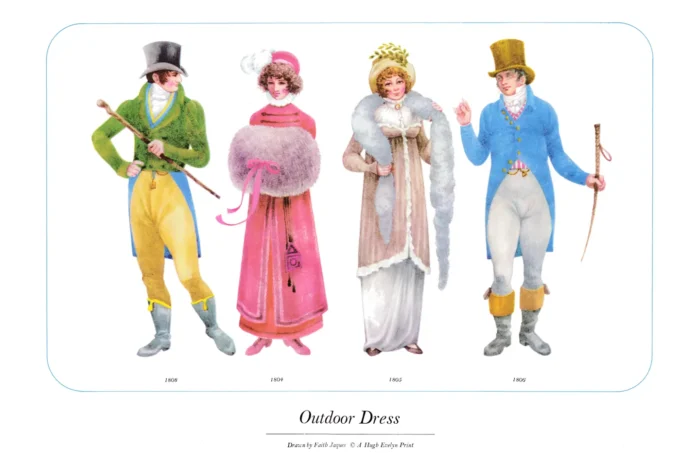

Outdoor Dress, 1804-1808

£5.00

Outdoor Dress, 1804-1808 (scroll down for a more detailed Description)

Published 1966 by © Hugh Evelyn Limited; drawn by Faith Jaques

Size: c. 38 x 25.5 cm [15″ x 10″] may vary slightly from printers’ cut 50 years ago

Printed on white matt medium cardstock weighing 148 g/sm2

Print is STANDARD size – shipping is the same for 1 to 10 prints (based on largest print size in your order) – see Shipping & Returns.

In stock

Description

With the coming of the 19th century the Englishman became, and has ever since been, the arbiter of fashion in the male western world. The Italian, American and our own adolescent crazes may come and go but the well-dressed man at any important function still has the flavour of Savile Row about him. The English were always avid travellers and could exhibit them selves in their comfortable practical clothes – more suitable for the harder life of a democracy than the more gorgeous modes still worn on the Continent. As has already been said, the Englishman was already wearing plain cloth coats, except for court functions, well back in the 1790’s. The country squire’s entire appearance became the fashion for several reasons. The British were always country-lovers and all the important folk spent as much time on their estates as in their town houses, and it is natural that their clothes should be practical for both spheres. Our public schools were probably tougher than any modern Borstal and a man had to develop muscles to hold his own. Gradually there evolved a cult of physical fitness which, allied to an educated intelligence, gave the happy owner an air of independence and authority that has been the envy and irritation of other nations until recent times when, alas, the Englishman has begun to have doubts about his behaviour and appearance. These lordly creatures were well served by their tailors who were used to handling heavy cloth (this being the country of origin of fine woollens) and were therefore more adept at dealing with material and more expert at fit and cut than the French tailors whose patrons still favoured silks and velvets. Above all, the woollen cloth, with the cunning inventions of front stiffeners and collar lifters, stayed in shape much longer than lighter-weight materials. With the coming of the classical vogue all man could do to follow the rage was to make his clothes as tight as possible and shorten his waist-line so that his athletic legs looked as long and sculptured as possible. The cult for athleticism and sport was actively indulged in by rich and poor, the rich being that much more professional due to painful hours of exercising in boxing, riding and in the gymnasia. These last were run by famous pugilists who in many cases by their simple dignity were able to mix with their aristocratic patrons on a level of friendly intimacy. Lord Byron snobbishly stated that he preferred them to his college acquaintances. So great was the passion to appear like the finest of these sports men that the neckcloth of one of the most popular pugilists became the height of fashion and was adopted as a type of cravat – the Belcher. A portrait of William Jackson, ‘Gentleman Jackson’, painted by Benjamin Marshall in 181o, in high breeches, silk stockings and cutaway coat as if for a court function, shows the epitome of the athletic style that all the young bloods emulated and the cause of the fluttering in the little low bodices of their girlfriends. Running neck and neck with the athletes in the dictates of fashion was, of course, the horse. The English country man took most of his pleasure in its company, besides which it was the only means of transport in country or town. Long boots had been invented many generations before to protect the legs in their thin coverings, and with all the intriguing styles to copy and good bootmakers to manufacture there was no need for dullness about the legs and feet -in Hessians, Wellingtons or jockey’s turned-over tops. It was about this time that breeches, which had always been practical for leaping on and off a horse, were lengthened to tuck into the top of the boot and were fastened by strings or laces, as a change from the loosely buckled knee-breeches of the previous century. To avoid an embarrassing split they had to be made of some stretching material -stockinette or soft doeskin which, so we read, were even fitted wet, to take the lines of the figure. The closure was like a square flap and was fastened by button with fobs either side and, later, embellished with braiding or embroidery in the hussar tradition. Even the pockets were designed with the horse in mind. Where a horizontal slit had been suitable in the skirts of coats, the pockets in breeches had to slope sideways so that the rider could nonchalantly tuck his fingers into the slit or extract money without an awkward overhand movement into a straight opening. The jacket was still the country riding coat with the front cut away for greater ease and graceful fit when sitting on that tyrannous horse. Influenced by the classic line it became shorter in the body and, either single- or double-breasted, was generally cut square across the front. In case it rode up in movement, a light-coloured vest, or waistcoat, was prolonged to cover the top of the breeches. Early in the century these were striped, as in the Directoire fashions, but later were white or pale-coloured. These waistcoats, also confusedly called gilets, had collars with indented lapels that stood up as high as the coat collars and were often turned back over the rolling outer collar. With a frilled shirt, high standing shirt collar sawing the ears, and wound round with an enormous cravat, the likeness to the giraffe women of Burma was complete and bending the head well-nigh impossible, but the air of superiority was crushing and well worth all the inconvenience. Even the hat owed its shape to the equine fervour of the English. The late 18th century tricorne was made to perch on the head and was therefore inconvenient in a high breeze. The English round hat with semi-soft brim was jauntier and, conical, sugarloaf or with a spreading topped crown, could be rammed down on to the head and made a useful crash helmet into the bargain. As the main thickness of clothes was round the chest and neck long cloaks or overcoats, the surtouts, covered all this grandeur and, from the coachman who needed extra warmth round the shoulders with freedom for the arms, the glorious caped coats were borrowed. The Spencer also acted as extra protection, with its short sleeves and short, or cut off, tails it was often worn over the riding coat. Great play was made with sticks and gloves while buttons in pearl or steel were very important on these otherwise plain garments. With the use of more solid and practical materials in men’s clothing the colours automatically changed and, except for the ‘pink’ of hunting coats, never again till this day of the modern exhibitionists has man worn the bright shades he sported up to the early 19th century. The famous Beau Brummell has been credited with the responsibility of introducing dark clothes but we hear that he always wore a bright blue coat adorned with shiny buttons. What can be traced to his influence was the sudden importance of cleanliness and the fact that a fine cut, spotless linen and shining boots outshone a more extravagant but tawdry appearance. The French guyed John Bull as well as his lady but gradually the simple fashion became the vogue for all Europe. The Classic line for women had by this time turned into something more suitable for the northern climate and a workaday world. Gooseflesh is never very becoming so sleeves made their appearance and the low neckline was filled in with a little chemisette. The Gothic revival and Romantic movement were beginning to penetrate the consciousness of the ordinary man through the flesh creeping novels of Mrs Radclyffe. Puffs began to appear on the tops of sleeves, and the chemisettes carried little ruffs which were later to develop into full Medici collars. The tunic dresses were the first step towards a heavier over-dress which, with a front closure, made a warm house-dress called the ‘douiette’. In heavier material it became a surtout, or redingote, in imitation of the male fashion, even to the tabbed fastening and small cape with a high-standing collar. The romantic swagger of the Hungarian Hussars had been copied by all the mounted regiments of the European countries, Napoleon’s generals fitting themselves into these jaunty garments as to the manner born, and even the solid British regiments were not above a bit of Ruritanian glamour. The cut and trimming of these military garments caught the imagination of the leaders of fashion, and men and women alike burst into frogs and braid down every seam, across coat fronts and around every pocket. The last vestige of this vogue can be seen down the seam of modern evening dress trousers. Muffs had appeared through many centuries: for warming the hands, as an aid to coquetry or for carrying pets. It is difficult to see the influence that made these so large at the beginning of the 19th century other than the simple one that, with the slim outline and a long train, the muff was a good balanced design. Our Russian allies or the Hudson’s Bay Company probably supplied the bear-skins with which these were made. Stoles had to be slim so as not to detract from the long vertical lines of the figure, and the bird world was the chief supplier of the swansdown, marabout and grebe, for these forerunners of our grandmother’s boas. Both men and women drew their hair forward in coiffs and fringes, with little curls on the women following the sideboards of the men. With their outdoor garments both the women in our picture are wearing hats; soft crowns and little turned-back brims, or bands, but no fastening under the chin as in capots or bonnets. Our old friend the reticule (from reticulate, netted) appears again in a square shape with long drawstrings and tassels. The fact that the French dubbed it the ‘ridicule’ gives one to think that, like the cardigan, it was something dear, especially, to the heart of the Englishwoman.

Additional information

| Dimensions | 38.1 × 25.5 cm |

|---|