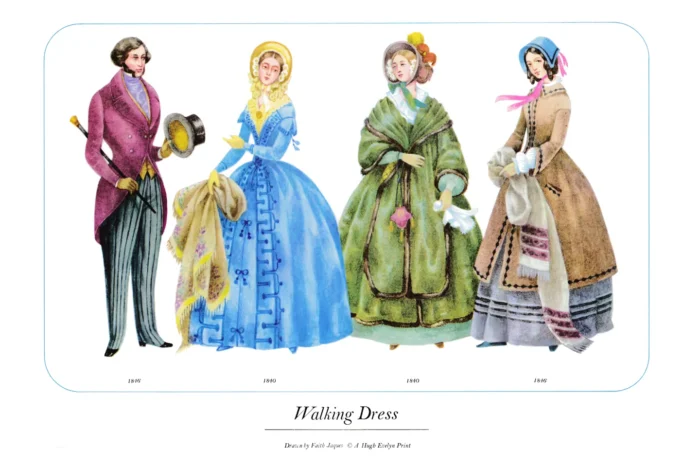

Walking Dress, 1840-1846

£12.00

Walking Dress, 1840-1846 (scroll down for a more detailed Description)

Published 1966 by © Hugh Evelyn Limited; drawn by Faith Jaques

Size: c. 38 x 25.5 cm [15″ x 10″] may vary slightly from printers’ cut 50 years ago

Printed on white matt medium cardstock weighing 148 g/sm2

Print is STANDARD size – shipping is the same for 1 to 10 prints (based on largest print size in your order) – see Shipping & Returns.

In stock

Description

By 1840 the new social order, which had been rising since the late 18th century, had become consolidated, both in England and on the Continent, and it is the behaviour of this new society that we see reflected in the clothes and furniture of the period. For it is the demand for, as well as the acceptance of a style by a majority that makes any change in it the fashion. When there was a clear dividing line between the classes of nobility and the workers, fashion was confined to the former (the lower classes wearing a simple copy of the shapes worn by their betters), with the result that clothes were more flamboyant and rich and a man’s position could be gauged by his coat. It was not considered ostentatious to be richly dressed; the demand was for outstanding styles in the great competition of grandeur amongst one’s peers. With the great leavening of the classes that began with the opening of the century the attitude to showiness changed. Power was now in the hands of the bankers and merchants who had feathered their nests during the wars, and of the manufacturers who found themselves in the delightful and comfortable position of sup plying the demands of a vastly increased spending community. These people, especially in England, represented the now established middle class; for the most part genuinely observant of the Commandments of the Old Testament and the strictures of St. Paul (having been stirred by a great Evangelical Revival), they had no desire for the frivolities of the leisured class, and if they did buy themselves into society they took with them their solid respectable way of life. They demanded worth for their money, and as their suppliers were of the same background what they got was worthy, solid and of an appalling tastelessness. Meanwhile the nobility and upper class, no longer having the monopoly of grandeur, took refuge in an exclusiveness of manners. To be distinguished by manners was less ridiculous, in the new plutocracy, than to be noticed by rich apparel that could be copied, and even excelled, by those of lower birth but equal means. With this new attitude to ostentation began the idea of ‘good form ‘, an attention to detail and what was considered the ‘˜right thing’ by the leaders of society. As the new-rich entered the ruling class and learnt the rules of the game the first real inter-class snobbery began: those in the know and those just arrived determined to keep the others out. Both these influences – the demands of the commonplace community and the idea of conformity to the rules of the ‘old school tie’ – made costume soberer and less adventurous. The way of life had changed, too, with greater mobility assisted by the coming of the railways and an increased business and office activity. Clothes gradually fell in line with suitability to circumstance. The mackintosh had been invented in the late ‘twenties, and with this a man could scorn the effects of weather on his expensive cloth, being no longer dependent on carriage and horses. The dominance of this comfortable middle class, family-conscious, plain and upright-living, profoundly affected the life and appearance of woman. The support of that sacred edifice, the family, was the man, and under this heavy patriarchal system woman, uneducated and yet unsuited to share any burden of existence other than reproduction, retired behind the curtain of domesticity; in this, paradoxically, she repeated the way of life of the ancient civilization far more than during the time when, in the early years of the century, she had assumed the dress of and imagined herself a Greek goddess or a Roman matron. Man’s lesser half, conforming to the rules of ‘good form’, had above all to appear like a Lady, capable only of domesticity, demure and feminine. Feminine, that is, to the eyes of the master of the family alone. Tantalising curves and undulations were now firmly encased in layers of flannel, stiff linen and whalebone and tightly laced out of harm’s way. Women’s dress assumed a line more functional and as little figure-deforming as it had been for many years and at the same time conformed to the current ideal of womanly gentility – and our modern conception of prudery. There is no question that the line was becoming, if insipid, and inspired by the dress of the Cavalier period (another occasion of the eclipse of the female character). The shoulders sloped into low inset, simple, tight-fitted sleeves, the decolletage was framed in a large collar, or bertha, of beautiful handmade lace (although even a replica of this was within the means of the less wealthy from the lace looms of Nottingham) and the waist dipped from the gently swelling bust into a tight stem from which the skirts flowed like a down-turned flower. By 1840 the skirts began to widen, and, to conceal the line of sex stimulating legs, woman added to her burden by wearing innumerable petticoats which also gave the silhouette a more pleasing shape. Over long lace-trimmed drawers, chemise etc. came a petticoat of flannel, one of linen stiffened with horsehair, and several of embroidered cotton, flounced to give the dress the upturned lotus look. As the skirts spread wider whalebone was threaded through tucks in the linen petticoat, in an increasingly wide circumference, as a more solid construction under the flounces. Several layers could be sewn into one waistband, but even so the weight must have been oppressive and the habit of lounging understandable. The problem of covering this bell-like structure was resolved by the old standby – the square shawl. The looms of Paisley copied the old Kashmir designs in increased quantity while the genuine article could fetch enormously enhanced prices. So essential was this article to a woman’s toilette that one was generally given with a trousseau and was of such excellent quality that several generations wore it with comfort and style. For more protective wear a mantle was devised, influenced by the peasant cloaks of various middle-European countries and even the North African burnous. The fronts fell full from the shoulders which were swathed in a fichu-shaped collar with ends reaching to the hem. The sleeves were cut in one piece with the body and were generally short and full in what we know as the Magyar style. The back was fitted in to the waist and flowed in pleats or gathers over the full skirt. The mantle was so practical and popular that it continued in use, on and off, for many years and still graces the title of its maker’s Trade Union. A trifle more dashing in line were the coats and tunics that followed the exact shape of the dress, demurely collared in white lawn and bow-tied at the neck. The hair now framed the face and drooped in curls or loops over the ears, being covered during the day, in the case of a married woman, with a little frilled cap that followed the line of the hair and met under the chin in muslin and lace tie-ups. That symbol of womanly effacement, the good poke bonnet, now bent its ampler brim concealingly round the cheek and almost met under the chin with wide satin ribbons and allowed only tantalising glimpses of lace frill, shining curls and rosebud features – a very cunning instrument of allure. Male costume varied little from the previous generation. The lapels rolled wide from the neck and the waist was pinched but the collar and stock no longer sawed the ears. The top hat (tall and waisted like the coats), cane and gloves played a great part in the intricacies of etiquette. According to a guide book of the time neither might be left in the hall in paying a visit, unless one were a friend of the family of long standing but had to be carried into the drawing room and manipulated along with a cup of tea and wafer-thin bread and butter – a performance of ritual well worth watching, one would think.

Additional information

| Dimensions | 38.1 × 25.5 cm |

|---|