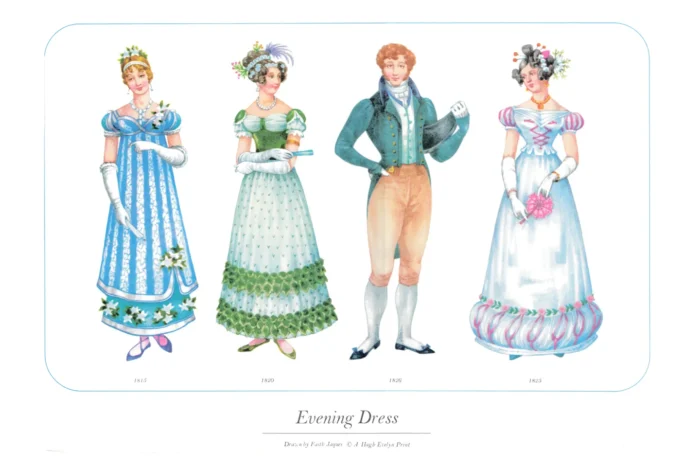

Evening Dress, 1815-1826

£12.00

Evening Dress, 1820-1826 (scroll down for a more detailed Description)

Published 1966 by © Hugh Evelyn Limited; drawn by Faith Jaques

Size: c. 38 x 25.5 cm [15″ x 10″] may vary slightly from printers’ cut 50 years ago

Printed on white matt medium cardstock weighing 148 g/sm2

Print is STANDARD size – shipping is the same for 1 to 10 prints (based on largest print size in your order) – see Shipping & Returns.

In stock

Description

The passion for distraction, so evident after every war, made evening dress more usual after 1815. The bourgeoisie had arisen in France, and in England people who would have been very lower middle-class had acquired fortunes from trade and commerce with the East and West Indies. The demand for more material boosted the weaving industry and the evil age of sweated labour began. The newly rich, or near rich, hankered for the pleasures they had seen enjoyed only by the rich in former years, and as their fortunes were not quite equal to the strain of entertaining on the scale of the previous landed gentry, those public functions became more common to which the middle-class could flock and be seen in the fashionable clothes that only the rich had worn till this era. Balls appear to have been the rage, as the dancing mania gripped the public after the privations of the Napoleonic wars. Much time must have been spent at classes, learning the figures of the set dances, as in our own jazz age, and the contemporary prints of dancing in the Assembly Rooms such as Almacks show it to have been equally energetic and grotesque. Fashion at this time was a whim created by the cultured and sophisticated, and according to their attitude to current feeling so trends appeared in clothes and gradually filtered down to the masses, who wore them quite oblivious of the origin of the style they slavishly hurried to follow; quite the opposite from the modern practice, where fashion is hammered out on the drawing board and every idea is exploited in a vast, commercial network. Romanticism had gripped Europe by the 1820’s as a revulsion from the Imperial ideal, fed by the literature of Sir Walter Scott in England and Schiller in Germany, and eagerly assimilated by the French. All the popular books were on medieval adventure, and again, as in our own times, a feeling of unrest and loss of purpose turned the public to a morbid escape in tales of horror and distress. After literature, fashion is the first social medium to reflect the spirit of the age, as it is the simplest method of showing one’s feelings and inclinations. This was the end of robust paganism and the beginning of romantic melancholy. Byron, the darling of the intelligentsia and fashionable world alike, looked upon himself as doomed and the fashion soon caught on – to be interesting and pallid, as if pining with a secret sorrow. Tight lacing and vinegar did the trick for the women and the young men emulated the poet’s open collar and unruly hair. It must be remembered that social changes take many years to materialise, and while the off-beat idea will catch the fancy of the public its cause will be unknown and behaviour, to match the appearance, may take a generation to become universal practice. The morbid atmosphere had thickened over many years of the late 18th century and the early 19th but, to the ordinary man and woman, the fog was not going to close in for a good few years to come. Fussy innovations were accepted as a nice change and the Alderman’s wife, or wool magnate’s plump daughter, embraced the new vogue with a right good will, not dreaming, or caring, to what the tight lacing and romantic novels would lead them and their daughters in a few years’ time. There are always many more influences than one that change the appearance of a people. Ideas were a trifle mixed as to the exact period the fashions were copying at this time; but the trend was mainly to the 16th century with its slashes, puffs and ruffs. Interior design followed on, in tortured carved woodwork that only had a sketchy resemblance to the Gothic, and hangings became heavier, both in substance and in the trimmings of fringes and cords. The Perpendicular made its appearance, in clothes, by sharper angles, vertical decoration and points instead of rounded scallops. It was in the 1820’s that the first sway towards primness and prudery became apparent. The revulsion against the licence of the Directoire and Empire in France and the Hanoverian laxity in England was backed up by the rise in power of the middle classes who were stirred by a religious revival. This spirit always spells the end of women ‘s freedom, a thorny problem for the church ever since the days of the early, founding fathers. Flesh is a temptation and must therefore be covered up. It is from this time that clothes became modest and the demeanour demure. The earnest guardians of our social morals never seem to win. Uncovering lets loose unbridled licence and covering up breeds unhealthy practices. Man, never able to strike the happy mean, has wisely tried a little of both alternately since clothes were first worn. Necklines at this period, even in evening dress, rose higher, and jewellery was heavier and covered the throat as much as possible. The Gothic angles can be seen in the bodices, with fullness taken straight across the high front to the shoulders where it joins the sleeves in sharp curves. Arms had to be covered, so long white gloves became an essential part of the whole toilette. These could be beautifully made by hand, with embroidered backs and fancy stitches on the seams. The fan made its reappearance, to aid coquetry in that strange conflict between inclination and the acceptance of repression. There could hardly have been a style more contrary to that of the Empire than the Valois, or our Elizabethan, with its tight long body and bell skirts, and the transition was slightly ludicrous. To make skirts conform was simple, by the wearing of more petti coats and the hem line stiffened and widened with ruchings, puffs and cords; but the little high bodice was more of a problem and corsets had to be introduced to draw in the unruly ribs and the comfortable roll, underneath, that had surely developed with the abandoning of a waist line. As the waist lengthened and tightened, so the shoulders and sleeves widened to give the illusion of slenderness under the ribs. Again, we can see in our illustration the gradual change and the slight confusion of ideas in the trend. On the one hand we have the vaguely Teutonic, peasant, laced bodice that might have been worn by Goethe’s Marguerite, and the puffs and gathers of Mary Stuart on the other. Fancy dress balls were the rage, we are told, but one wonders why they bothered to dress up when every day dress could be, and was, so histrionic. Hair styles sturdily resisted the return to the Valois and, although now with a parting, curled profusely round the face and rose in knots to the crown of the head to be entwined with ribbons, small feathers and flowers. All these elaborate clothes, it must be remembered, were made laboriously by hand, in fine seams and tucks, with reinforcement of linen and covered in eyelet embroidery by the increasing labour force of sempstresses in the workrooms of the modiste many years before the invention of the sewing machine. For formal occasions, man obviously felt more at home in his breeches. Why the showing of his leg should enhance his air of distinction we shall never know, but this style, with the wearing of silk stockings, was revived in the ‘eighties at a period of great affectation and has been accepted, and has remained, as the highest formality in ceremonial dress until today. The same may be said for the strange hat, the chapeau bras, which made its first appearance at the time of the Revolution. Like a wide-brimmed felt that has been turned up back and front and sat on, it was carried under the arm or worn, but it was never permissible to put it down. Worn, it was remarkably gallant as we see from the portraits of Napoleon’s generals, and as a useful instrument of the graceful gesture it must have been a boon to the Englishman who has never known what to do with his hands.

Additional information

| Dimensions | 38.1 × 25.5 cm |

|---|