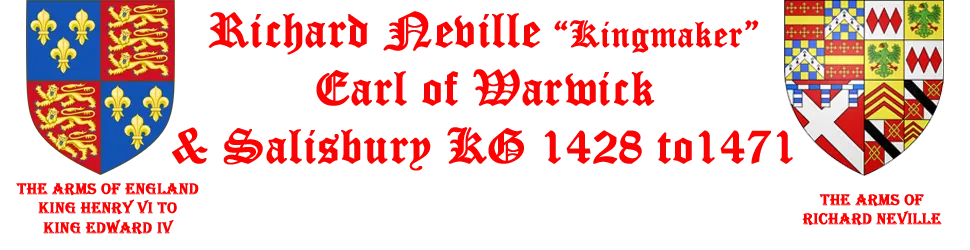

Richard (“The King Maker”) Neville, Earl of Warwick and Salisbury, K.G., 1428-1471

Original price was: £35.00.£25.00Current price is: £25.00.

English nobleman called “the Kingmaker,” in reference to his role as arbiter of royal power during the first half of the Wars of the Roses between the houses of Lancaster and York. He obtained the crown for the Yorkist king Edward IV in 1461 and later restored to power the deposed Lancastrian monarch Henry VI Published 1966 © Hugh Evelyn Limited; artist John Mollo (1931-1917); c. 36 x 53 cm (14″ x 21″) heavy white matt cartridge paper (157 g/sm²); Shown here is a scan of the print. This is a LARGE sized print; see mail costs at Shipping & Returns.

Detail below

In stock

- Satisfaction Guaranteed

- No Hassle Refunds (see Shipping and returns)

- Secure Payments

Description

SUMMARY

One of the Yorkist leaders in the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487), Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick (1428-1471) was instrumental in the accession of two kings, a fact which later earned him his epithet of “Kingmaker” to later generations. The Wars of the Roses were a series of English civil wars for control of the throne of England fought between supporters of two English rival branches of the royal House of Plantagenet: The House of Lancaster (associated with a red rose), and the House of York (whose symbol was a white rose). Through fortunes of marriage and inheritance, Warwick emerged in the 1450s at the centre of English politics. Originally a supporter of King Henry VI, a territorial dispute with the Duke of Somerset led him to collaborate with Richard, Duke of York, in opposing the king. From this conflict he gained the strategically valuable post of Captain of Calais, a position that benefited him greatly in the years to come. The political conflict later turned into full-scale rebellion, where in battle York was slain, as was Warwick’s father Salisbury. York’s son, however, later triumphed with Warwick’s assistance, and was crowned King Edward IV. Edward initially ruled with Warwick’s support, but the two later fell out over foreign policy and the king’s choice of Elizabeth Woodville as his wife. After a failed plot to crown Edward’s brother, George, Duke of Clarence, Warwick instead restored Henry VI to the throne. The triumph was short-lived however: on 14 April 1471 Warwick was defeated by Edward at the Battle of Barnet and killed.

DETAIL

In his effigy Richard Neville is shown wearing a tabard [1], a sleeved garment which succeeded the tight jupon [2] after a short period during which it seems that no coat armour was worn. The tabard has been preserved as the official uniform of the royal heralds, who wear a tabard of the royal arms at state ceremonies.

The elaborate arms depicted on the tabard and repeated on each sleeve are those which appear on a seal of Warwick’s attached to a document dated 1465, six years before he was killed and at a time when he was regarded more as a king than a king-maker. The arms may be blazoned Quarterly: 1st grand quarter: sub-quarterly i and iv, Gules [3] a Fess [4] between six cross crosslets Or (for Beauchamp); ii and iii, Or three Chevrons Gules (for Clare); 2nd grand quarter.· sub-quarterly i and iv, Argent [5] three Fusils [6] conjoined in fess Gules (for Montagu); ii and iii, Or [7] an Eagle displayed Vert [8] (for Monthermer); 3rd grand quarter.· Gules a Saltire [9] Argent a Label company of the last and Azure [10] (for Neville); 4th grand quarter: sub-quarterly i and iv, Chequy[11] Or and Azure a Chevron Ermine (for the old Earls of Warwick); ii and iii, quarterly Argent and Gules a Fret [12] Or over all a Bend Sable (for Despenser). Thus in one achievement are to be found marshalled seven of the most ancient and famous arms in this country, arms which have formed the basis for numerous later coats of arms up and down the country. The order in which these coats are marshalled seems capricious at first sight and certainly does not follow the modern rules for assembling a variety of inherited arms on one shield. However, a certain method can be discovered in this apparent madness. Richard Neville married Anne, sister and heiress of her brother Henry Beauchamp, Earl and Duke of Warwick. On his death in 1450 Neville and his wife were confirmed as Earl and Countess of Warwick with remainder to the heirs of the body of Anne. This was Neville’s senior earldom and so it is not unreasonable that he should show the red shield with the gold fess and crosses of Beauchamp in the first quarter. What is surprising is that the gold and blue chequered shield with an ermine chevron, used by the old Norman earls of Warwick, should have been put in the last quarter rather than the first. Anne’s mother was Isabel, daughter of Thomas Despencer, Earl of Gloucester, which earldom had come to the Despencers through the marriage of Hugh (son of Hugh, Earl of Winchester) with Alianore, sister and co-heir of Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester and Hereford. Presumably it is for this reason that the gold shield of Clare with its three red chevrons is found quartered with Beau champ. The Nevilles became Earls of Salisbury because the kingmaker’s father Richard married Alice, daughter and heir of Thomas Montagu, Earl of Salisbury. The second quartering is, therefore, devoted to Montagu heraldry the three red fusils on silver of this family, quartering the green eagle on gold of Monthermer, the heiress of which family a Montagu had married. In the next quarter is the silver saltire on red of the Nevilles, differenced by a blue and white label to distinguish the line of Salisbury from the senior line of Montagu. In the last quarter are the arms of the earldom of Warwick, referred to above, and those of Despencer which should really be associated with the coat of Clare.

In marshalling the arms more regard has been paid to the importance of the heritage rather than to genealogical accuracy. On Warwick’s seal two crests are used, the swan of Beauchamp and the griffin of Montagu. Here the griffin is shown. At Warwick’s feet are the Monthermer eagle and a shield of the Neville arms as shown on one of Warwick’s later equestrian seals. The shield is of the new scalloped type with a piece cut out of the right-hand side, this being the lance-rest. As Warwick’s arms indicate, he was born great; he then married into an even greater family and, by his own talents and ambition acquired a measure of greatness seldom enjoyed by a subject.

The history of Warwick is well known as it is the history of England during the wars of the Roses. He espoused the Yorkist cause, hence the collar of roses about his neck, and supported his brother-in-law Richard, Duke of York, who claimed the throne through his mother, the heiress of Lionel, Duke of Clarence, third son of King Edward Ill. During the temporary insanity of Henry VI, York had ruled with moderation and impartiality as protector of the realm, but with Henry’s recovery he stepped down and saw Queen Margaret and the Beauforts restored to power.

The Yorkists took to arms and regained power by defeating the king’s forces at St Albans in 1455. After this, Warwick worked hard to reconcile the opposing sides and the result was the great love-day procession at St Paul’s to which Warwick came with a vast band of men ‘all arayed in rede iakettys with whyte raggyd staues upon them’.

The peace was short lived and in 1460 Warwick led the Yorkists at the victory of Northampton after which the king disinherited his son and named York as his heir. But the queen rallied her forces and the battle of Wakefield brought terrible carnage; the Yorkists were routed and their leaders slain. ‘Be-done-by-asyou-did’ was the rule and Edward, the new Duke of York, avenged his father’s death at Mortimer’s Cross.

However, at the same time, Warwick was soundly beaten at St Albans but managed to escape. The queen now committed a tactical error by marching north; this left London open to the Yorkists and they were received there with rejoicing. Warwick now made a king by acknowledging Edward as King Edward IV at Baynards Castle, close to where Blackfriars station now stands. To be king in fact as well as in name Edward had to destroy the queen’s army and this he did at Towton.

After this holocaust Edward was crowned and Warwick, loaded with Lancastrian spoil, became the first man in the realm. After finally crushing the Lancastrians he ruled the land wisely whilst the young king relaxed and enjoyed himself. Whilst Edward did this Warwick was happy, but when the king married Elizabeth Wydeville, showered favours on her mere but numerous relatives and made an alliance with Burgundy rather than with potentially dangerous France, Warwick was forced to remonstrate and eventually to subdue the king. Warwick now had two kings in his power, but it was to Edward that he restored the throne after promises of reformation and the issue of free pardons. Warwick did not trust Edward, for he and Edward’s brother, the Duke of Clarence, who married one of Warwick’s daughters, were proclaimed traitors. They retired to France, made an alliance with Queen Margaret and landed in England. The country rose in their support; Henry was restored and Edward fled to the court of Burgundy to plan his next move.

He did not wait long, but returned to England, landing in Yorkshire. He marched south, gathering support as he came. The inevitable battle was fought at Barnet in 1471 and it was here that the great Warwick fell and with him the Lancastrian cause, which was finally lost at the battle of Tewkesbury a few weeks later.

The armour shown in Warwick’s effigy is like that which he wears in his last equestrian seal. In place of a bascinet he wears a sallet[13] with moveable visor and, at his elbows, large bracelet-type couters[14]. His effigy also incorporates a feature associated with the second half of the fifteenth century, the wearing of the great sword in front of the body from a sling round the waist.

[1] A short surcoat open at the sides and having short sleeves, worn by a knight over his armour, and emblazoned on the front, back, and sleeves with his armorial bearings.

[2] A close-fitting tunic or doublet; esp. one worn by knights under the hauberk, sometimes of thick stuff and padded.

[3] Red.

[4] An ordinary formed by two horizontal lines drawn across the middle of the field, and usually containing between them one third of the escutcheon. [An ordinary is a charge of the earliest, simplest, and commonest kind, usually bounded by straight lines, but sometimes engrailed, wavy, indented, etc.]

[5] Silver.

[6] A bearing in the form of an elongated lozenge; understood to have been originally a representation of a spindle covered with tow.

[7] Gold.

[8] Green.

[9] An ordinary in the form of a St. Andrew’s cross, formed by a bend and a bend sinister, crossing each other; also, a cross having this shape.

[10] Blue.

[11] Divided into several rows of squares of two alternating tinctures.

[12] A figure formed by two bendlets, dexter and sinister, intersecting.

[13] In mediæval armour, a light globular headpiece, either with or without a vizor, and without a crest, the lower part curving outwards behind.

[14] Pieces of armour to protect the elbow.

Additional information

| Dimensions | 37 × 54 cm |

|---|